My journey into game development

I often get the question how I got into game development and if I have any tips for beginners. Here’s my story and thoughts about getting into game development.

Childhood

I’ve never been particularly interested in playing games myself. I never had a gaming console as a kid, but ever since I was very young I’ve had a strong interest in engineering and technology. My early interest in computers was entirely centered around programming, and not playing games.

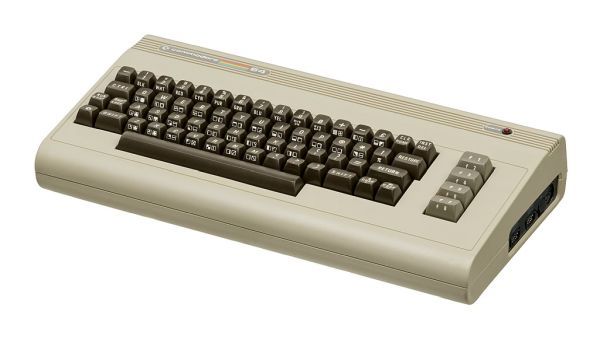

I somehow convinced my parents to get me a Commodore VIC 64, because that was what one of my friends had. I’m not sure how old I was, but I must have been eleven or twelve. Back then, the printed manual for a computer was an introduction to programming (BASIC, in this case). When turning the computer on, there was a prompt where you could start programming. Overall, the bar to enter programming was way lower than now. No choice of programming language, no game engine, no downloading and installing stuff, you just turned the computer on and could instantly start programming (like, literally instantly, the interpreter was burnt into a ROM chip).

Programming languages sucked, performance was terrible and debuggers non-existent. If you made an error, the computer froze and you had to turn it off and back on again and start over. It was frustrating, tedious and very unintuitive, but at the same time an excellent introduction to how computers work. In order to put a sprite on the screen, you had no choice but to map out each pixel on paper, learn binary numbers, convert that to decimal and load it into a specific memory address. Since there were no tools, everything was cumbersome, but at the same time, everything also seemed within reach without having to learn that much. There was only one way to do things – the hard way.

A few years later I upgraded to a Commodore Amiga 1000 and a whole new world opened up. This was much more similar to computers as we know them today, with a proper desktop, multi-tasking, a file system, etc. It shipped with a programming language (AmigaBASIC), but for some reason I never really got into it. Instead, I got introduced to the AMOS programming language, which I remember as an absolutely fantastic environment for learning to make games. It had a lot of built-in functionality for doing the most basic things, like loading images, playing sounds, drawing lines, etc. It also had the ability to execute inline assembly code which made it very powerful.

Getting better at programming and learning the hardware I got more and more comfortable programming directly in assembly language instead of AMOS and finally swithed over to using AsmOne as my default programming environment. In retrospect this was a terrible move, because writing everything in assembly language is overly complicated compared to using something like C and just use with assembly were needed. I think this poor decision was mostly because I simply didn’t know that C existed, nor how to combine it with assembly. Remember that this was before the Internet was a thing, so the only knowledge you had access to was through your friends and good dose of curiosity and trial-and-error.

University

There were no game educations available in Sweden at the time, and I’m not sure I would have chosen one even if there was. At this point I had not decided on a career in game development, maybe because game development wasn’t really seen as a career option at all, so I went for a more traditional engineering program – Master of Science in Media Technology at Linköping University. This is where I first got in contact with object oriented programming through Java and later C++. I took classes in linear algebra, data structures, 3D rendering, physical modelling and animation, physics, acoustics, etc. It was definitely a good foundation for a game developer, even though this wasn’t a game centric education.

It was at university I developed a passion for game physics. I can’t remember exactly what caught my attention, but I wrote my first rigid body simulator in 1998, inspired by the papers on impulse based dynamics by Brian Mirtich. At this time physics was rarely seen in video games. The only one I remember studying intensely was Carmageddon 2, which featured incredibly sophisticated rigid body simulation for a game at that time. My first simulator was written in Java, with collision detection in C through the JNI interface. It was later rewritten in C++ and featured a wrecking ball machine at a building site.

Game physics and middleware

For the final exam project at Linköping University I decided to make a game physics SDK with Marcus Lysén. It never really reached a usable state, but was enough to encourage us to form a company around it and develop it further. We teamed up with Jonas Lindqvist and founded Meqon Research. Around the same time, other physics SDKs started popping up. The first verison of Havok got released. Mathengine was already on the market, and there was Ipion (mostly known for being used in half-life 2), PhysX by Novodex, and the open source project ODE. Even though I wouldn’t admit it at the time, we had the weakest product, no experience and no money, but somehow we managed to release the Meqon SDK a few years later and got a couple of customers. Most notably 3D Realms licensed our technology for Duke Nukem Forever, which gave us the confidence and credibility to push forward and grow the team to about a dozen people. All in all a very fun and intense period of my career, but completely unsustainable, stressful and unhealthy.

In 2005, Meqon was acquired by AGEIA and the whole team was integrated into the PhysX machinery. I worked as one of three software architects and got the chance to work with some incredibly talented people across the world, many of them I’m still in contact with today. This was a fantastic journey and undoubtedly an important cornerstone of my career. The people I worked with at AGEIA also influenced my coding style in a very important way. Coming from an academic, object oriented programming background, I started to question everything when I got in contact with experienced game developers who routinely rejected most of that in favor of a more direct C-like programming style that I slowly started adopting myself and still use today.

I left AGEIA in 2007, just before they got acquired by NVIDIA to work on scientific visualization. At this point I also started working on my own C++ framework to use for future projects. It wasn’t a game engine, but more of a low level framework with the functionality needed to make a game engine, such as vector math, file IO, compression, geometry, input, audio, rendering, scripting, etc. Creating your own tech was already at the time considered doomed to failure (even more so today), but doing it was a lot of fun and was undoubtedly an important key decision in my career. With a programming framework that I wrote from scratch, thus knowing inside out, I could very quickly implement new ideas and projects on top of that without ever running into any limitations.

One of the first projects I created with the new framework was Dresscode, a game engine profiling tool that I later sold to RAD Game Tools (now reworked into a product called Telemetry). Even if the framework has been rewritten and improved upon in several iterations, I’m still using it today for almost everything I do.

Indie game development

Up until this point I never really made an actual, released game, but that changed in 2010, when I teamed up with Henrik Johansson (one of the people I hung out with in the Amiga days) and founded Mediocre. Going from game technology and middleware to making actual games was equal parts fun and frustration. I had no experience with game design, but started appreciate it more than I thought I would. An interesting thing to note here is that both Henrik I had very little interest in playing games. We were not gamers, which I think is quite unusual for game developers, but it is my firm belief that playing games is orthogonal to being successful at making them. There are great developers who play a lot of games and there are great developers who never play games. Playing a lot of games is not a bad thing, but it does not make you good at making them, it makes you good at playing them (and this probably applies to a lot more than game development).

We did our first game, Sprinkle, as a part-time project while still doing contract work on the side to sustain our living and I think this was a really wise decision which allowed us to experiment and iterate on the game design to find something unique, with no real time pressure. It also allowed us to spend that extra time polishing the game prior to release.

I think the primary reason Sprinkle became successful was because we found something uniqe, but as always it’s hard to pinpoint one single factor. We had good timing, both because the App Store and mobile gaming in general was still young, and not very exploited, but also because there was a general interest in indie games at the time. Previous connections from NVIDIA and Meqon also contributed to getting us introduced to Apple and Google prior to release, thus increasing our chances of getting featured.

There’s a lot more to the story, including the other Mediocre games and everything that led up to Teardown, but I think I’ll stop here, since at this point I’m already a full-time indie game developer.

Advice

For learning programming and game development today I don’t really feel like I’m in a position to give beginner advice, because the conditions today are so different from when I started, but for programming in particular, it is my firm belief that experience is the most important factor. Write a lot of code and you’ll eventually get good at it. A good way to do this is to find a way to enjoy it rather than just trying to learn it. My career took a giant leap when I finally embraced that and focused on what I love the most – doing low level stuff and building things from scratch, but it may very well be something else for you.

As an indie developer you will often hear the advice to focus on marketing, otherwise you’re doomed. I don’t agree with that. Making a indie game is hard. Marketing an indie game is even harder. Marketing a mediocre indie game is nearly impossible. If you’re good at making games, focus your efforts on making a unique, fun and polished game instead. If your game isn’t appealing, make another iteration on the design, revisit the mechanics, the art style or whatever you’re good at until it has something that other games don’t. I think indie developers generally have a better chance of making a game that markets itself rather than trying to market a game that just isn’t very good.

Making something unique is probably the most important aspect. As a small developer you cannot realistically create a clone or even a variation of an existing game and expect it to be better than what’s already out there. With a tiny team you also cannot compete with large amounts of content, nor with technology. Originality is pretty much the only aspect of a game that works in your favor, so embrace it. Keep the scope as small as possible and polish until it shines in the dark.